Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax): 5 Things to Know

August 23, 2017

Wi-Fi

initially was 1x1 — a single stream, with a single client talking to a

router — but it has evolved into an 8x8 MIMO (multiple input/multiple

output) solution where multiple clients talk to a router at the same time. The

current Wi-Fi standard, 802.11ac (now called Wi‑Fi 5), was fully released in late 2013, and

it works very well in a home environment. But as with previous Wi-Fi

standards, it may reach its limits around 2022 when there could be 50 nodes in

a home, per the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Wi-Fi

initially was 1x1 — a single stream, with a single client talking to a

router — but it has evolved into an 8x8 MIMO (multiple input/multiple

output) solution where multiple clients talk to a router at the same time. The

current Wi-Fi standard, 802.11ac (now called Wi‑Fi 5), was fully released in late 2013, and

it works very well in a home environment. But as with previous Wi-Fi

standards, it may reach its limits around 2022 when there could be 50 nodes in

a home, per the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

802.11ax (now called Wi‑Fi 6) is the next evolution in the IEEE 802.11 Wi-Fi standard and will become prevalent in very dense environments, such as urban apartment complexes, college campuses, concert venues, or sports stadiums, where many clients will access the internet over Wi‑Fi. The IEEE standard currently is in development and expected to be publicly released in 2019.

Let's take a look at five key things you need to know about 802.11ax (Wi‑Fi 6) and the next generation of Wi‑Fi.

#1: What are the key differences between 802.11ac (Wi‑Fi 5) and 802.11ax (Wi‑Fi 6)?

- Uplink MIMO: 802.11ac supports multiuser MIMO, but only in downlink mode. In contrast, 802.11ax adds uplink capability, so multiple users can upload video simultaneously.

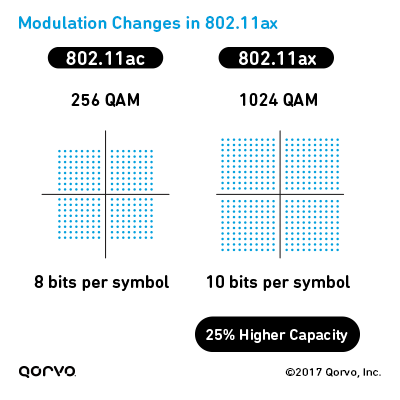

- Modulation: 802.11ax has a higher modulation scheme, moving from 256 QAM to 1024 QAM, which translates to better throughput and 25% higher capacity with 10 bits per symbol.

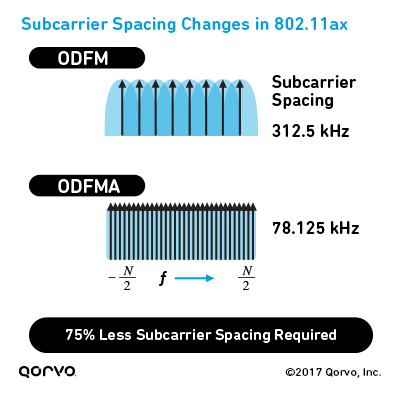

- Capacity and efficiency improvements: 802.11ax uses OFDMA instead of OFDM, which allows FDD versus TDD as well as resource unit allocation within a given bandwidth. Subcarrier spacing is also reduced to 78.125 kHz, which is 25% of 802.11ac spacing, and the symbols are 4 times longer. When combined, all these changes mean that the system is more efficient and can upload or download multiple data packets simultaneously, rather than one at a time.

- Schedule-based rather than contention-based: In 802.11ax, the access point dictates when a device will operate, thus handling clients more efficiently. Resource scheduling also significantly reduces the power consumption during sleep time, which improves battery life for clients.

See the table below for additional differences between 802.11ac and 802.11ax.

Glossary of Terms

#2: Wi‑Fi 5 (802.11ac) promises 6.9 Gbps but public Wi-Fi doesn't attain these speeds. Will Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) remedy this problem?

6.9 Gbps just isn't possible in a home or public Wi-Fi network. We will never see the theoretical speeds listed on the box of a router on the shelves at Best Buy, Walmart or other big-box stores.

The most limiting factor at home is the connection from the internet provider — the pipe coming into the home for internet access. If a router can support 1.6 Gbps but the connection to the home is only 100 Mbps, a client will never realize that higher speed for downloads from the wide area network (WAN).

The data stream into a home and the access point will establish the initial internet bandwidth benchmark. From there, other factors can slow the network speed:

- Distance between the client and the access point

- Interference from other clients on the same frequency

- Inherent Wi-Fi overhead for acknowledgments, transmit, and clear channel assessments

A Wi‑Fi 6 access point will provide a more efficient environment, mitigating the problems of Wi-Fi overhead — in other words, the fixed "cost" associated with the communication that isn’t a part of the data transmission. 11ax will attack the overhead differently, scheduling when a device operates and handling the information and clients more efficiently.

Additionally, advanced filtering techniques enable better coexistence and bandedge performance. This has two effects:

- Allows a broader spectrum to operate at full power

- Improves the quality of service and range in the once-limited bandedge channels

Altogether, improved efficiency and filtering will help 802.11ax have

faster speeds than 11ac.

#3: How does OFDMA create a more efficient payload delivery system?

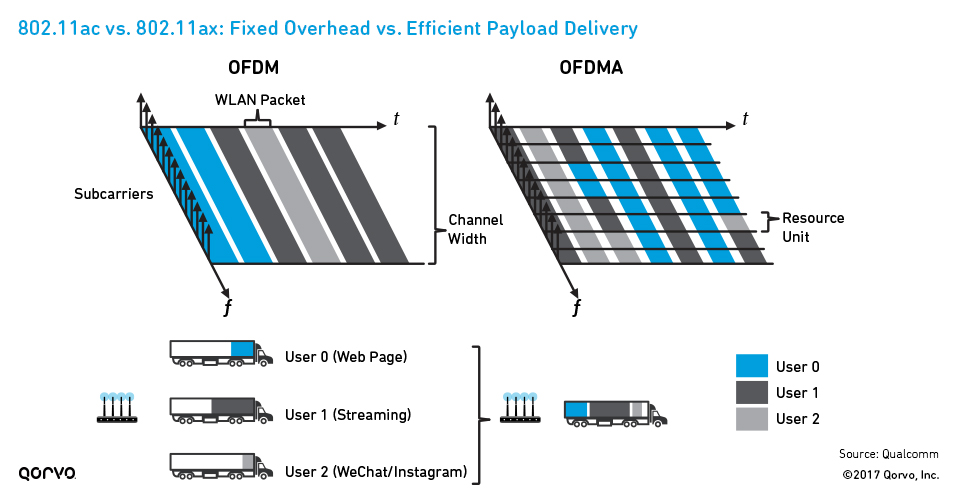

802.11a up to 802.11ac use OFDM, or orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing, to deliver Wi-Fi data packets. Under OFDM, a device uses a fixed 20 MHz or 40 MHz of bandwidth to deliver the packets, regardless of whether it's transmitting video or just sending a simple text message over a Wi-Fi network.

Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax), however, uses OFDMA, or orthogonal frequency-division multiple access, which allows resource units (RUs) that divide the bandwidth according to the needs of the client and provides multiple individuals the same user experience at faster speeds.

A simple analogy using trucks can illustrate the difference, as shown in the image below. Each truck is hauling a payload, or user data — one surfing the web, another uploading video from a soccer game and a third sending a text message, for instance. Under OFDM, a device had to use three trucks of the same size to send the data, regardless of how empty or full each truck was. In other words, OFDM inefficiently uses the bandwidth, leaving a lot of empty space. OFDMA, in contrast, allows a device to fill an entire truck with RUs (i.e., data) — a payload delivery model that uses the bandwidth much more efficiently.

#4: Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) supports 1024 QAM. What are the impacts of this higher modulation scheme?

With 1024 QAM modulation, there are more bits per symbol — 10 bits per symbol versus 8 bits in 256 QAM. More bits equals more data, and the payload delivery of data is more efficient — like having a bigger truck.

At the same time, OFDMA decreases the spaces between the subcarriers, packing even more resource units into the truck, so to speak.

But as the data rate increases, error vector magnitude (EVM) on the RF front-end becomes paramount. With 1024 subcarriers in Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax), the constellation is flooded and so dense that the system must distinguish one of the points from another. It takes a very sophisticated system to decode (or demodulate) these constellation points, and it requires devices to have better EVM.

Wi‑Fi 5 (802.11ac) requires -35 dB PA EVM, while Wi‑Fi 6

(11ax) requires -47 dB PA EVM. Higher modulation schemes require better

EVM so that a device can attain the higher efficiencies of the data

packet.

#5: What are the differences for Wi‑Fi 6 for a handset or other client versus access points?

As already said, Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) pushes the EVM requirements down to -47 dB, but access points and clients still have to meet the same spec. There’s no difference.

Power levels can be very different, though. Access points or customer premises

equipment (CPE) typically operate at much higher power than a

client — 24 dBm versus 14-20 dBm for a mobile handset.

Ultimately, a lot more power means a lot more heat

that has to be dissipated, so a connectivity solution may require a more

stringent thermal requirement compared to a mobile solution.

It's important to realize that the Wi‑Fi 6 (802.11ax) specification

is still in flux and won't be finalized for some time. Stay tuned for more

insights as the next standard of Wi-Fi continues to evolve.

Read more Wi-Fi design tips:

- 5G or Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax)?

- Wi-Fi 6: Wi-Fi Regulatory Roadmap and Beyond

- How BAW Filters Can Solve Key Design Challenges in the Transition to Wi-Fi 6

- Resolving Interference in a Crowded Wi-Fi Environment Using BAW Filters

Wi-Fi 6 is making the connected home of tomorrow a reality. See how Qorvo's "pod in every room" concept brings this vision to life. Watch Our Video >

Have another topic that you would like Qorvo experts to cover? Email your suggestions to the Qorvo Blog team and it could be featured in an upcoming post. Please include your contact information in the body of the email.